Dr de Meo, or How Kering (should) Learn to Stop Worrying and Hire SKMG

Issue 28: Gucci, we want a job

The luxury fashion industry is having its “oh shit” moment.

Yes, it’s always been a cyclical business, but right now sales are dropping, shares are tumbling and the traditional playbook of heritage mystique suddenly feels about as relevant as a Nokia 3310. But what makes this moment fascinating from a corporate communications perspective is that the crisis is forcing luxury brands to actually talk to people instead of at them.

The numbers tell the story. Kering shares have tumbled from their 2021 peak. LVMH Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton posted a 5% decline in first-quarter fashion and leather goods sales. Gucci revenue dropped 25% in Q1 2025. Meanwhile, the luxury customer everyone used to talk about isn’t buying luxury anymore, but they’re still shopping. High net worth individuals haven’t stopped spending – they've just stopped spending on high luxury as much, shifting toward brands like Post Archive Faction, Our Legacy, Aritzia and Arc’teryx that aren’t cheap but are cheaper than the big heritage houses.

This shift reflects something deeper: as Lauren Sherman observed in Puck, when luxury houses struggle, it often comes down to the fact that “fashion is not at the center of the culture like it was a decade ago. After all, nothing is any longer in the dawning, post-monoculture era.”

The holding groups are scrambling to adapt. LVMH continues playing the family-controlled mystique game while installing Arnault sons across various branches of the empire (who admittedly aren’t doing a bad job). Kering has taken a radically different approach: hiring Luca de Meo, the turnaround king from Renault, as its first external CEO. When the announcement hit, Kering shares soared 11.8% in a single day. Why? We’d wager it’s because the market finally heard someone speaking their language.

In the middle of all of this, almost two weeks ago we saw the (no real superlative could do justice)-anticipated Jonathan Anderson Dior collection hit the runway. As was expected (but not guaranteed) from high fashion's storyteller par excellence, it was a hit. But more so for its ability to read the room, and the market, than its pure creative vision.

Putting Anderson to one side for now, how do luxury brands spark smarter conversations when the traditional tools of exclusivity and mystique are losing their power? The answer lies in rewriting the relationship between brands and audiences – moving from customers to fans, from transactions to communities, from heritage lectures to two-way dialogue.

This shift creates massive opportunities for the brands smart enough to embrace radical transparency, authentic fan-building, and corporate communications that treat stakeholders like intelligent participants rather than passive recipients of carefully curated mystique.

Act

It’s not a smart conversation if there’s nothing to talk about.

Start with the right strategy and execution to prove you can walk the talk.

Why Kering hired a car guy to save luxury

De Meo’s appointment is fascinating. A 30-year veteran of the automotive industry is now charged with revving up a company that owns hallowed brands including Gucci, Saint Laurent, Balenciaga and Bottega Veneta. An energetic, fiercely ambitious executive, De Meo is taking on a group that has seen many of its brands decline and its share price nosedive since 2021.

As The Wall Street Journal pointed out, the guy is taking on a massive change: “[De Meo] must revive Kering’s core brands – starting with Gucci – while re-energising others such as Alexander McQueen. He’ll also need to manage Kering’s deepening debt and address longer-term questions about its portfolio, including its minority stake in Valentino and the option to buy the rest from Mayhoola, the Qatari firm that owns the majority.”

De Meo’s automotive background brings something many luxury “houses” need: strict financial discipline, a willingness to break pretty much every rule, a certain detachment from the weight of history, and the ability to talk the financial market’s language. He also has the ability to revive a company at a time of industry disruption (as he did in his five years at Renault).

This accountability culture contrasts sharply with many luxury houses’ traditional approach of focusing too much heritage storytelling and creative mystique. Family-controlled empires can operate with minimal external scrutiny. Listed companies cannot.

Success as a listed car company requires constant stakeholder education. CEOs must explain why certain models get discontinued, how supply chains optimise costs, which demographics drive growth, and what competitive threats justify strategic pivots.

Selling luxury goods, of course, is not exactly the same as selling a car. Convincing someone to buy a Renault requires a different strategy and conversation to convincing them to buy a Bottega bag. But the core business disciplines are – or should be – the same.

One clear opportunity for the de Meo-led Kering lies in implementing automotive-style stakeholder engagement, which leads us to presumptuously present *drumroll*

The SKMG-Kering automotive articulation playbook

(hire us Mr De Meo)

The opportunity

Treat luxury audiences like automotive customers: intelligent participants who deserve transparent information about business performance and strategic direction.

Phase one: get to the point

Replace luxury’s nebulous language (“brand evolution”, “creative transitions”) with precise problem identification. Address specific revenue declines, market share losses, and competitive disadvantages with measurable baselines that stakeholders can track independently.

Phase two: measure like you mean it

Establish quarterly reporting rhythms focused on what’s impacting the bottom line rather than vanity metrics. Track same-store sales growth versus competitors, customer acquisition costs by demographic, inventory efficiency rates, and geographic performance against industry benchmarks.

Phase three: strategic transparency

Communicate specific initiatives with defined success criteria and completion timelines. Enable stakeholders to verify progress independently rather than relying on management interpretation of subjective improvements.

Sure, it all sounds horribly dry, but when the fashion press is increasingly reporting like the AFR, you can’t be afraid to speak the language back. We would argue that consumers do have a vested interest in a brand’s performance: for many people, luxury houses are now like sporting teams (for one, creative directors and the NBA offseason share a fondness for musical chairs) and products like merch. People love to back the winning team.

Kering’s largest shareholder, François-Henri Pinault, explicitly stated that de Meo would have “full liberty to take the decisions that he wants” and wouldn’t be “short-circuited” regarding “his prerogatives, priorities or key appointments of the group”.

Unlike family-controlled luxury businesses where decisions reflect dynastic preferences, de Meo can drive shareholder value through, for example, a data-driven strategy. The corporate communications advantage lies in demonstrating measurable progress against objective criteria rather than subjective heritage narratives.

That will open up something companies in the automotive industry (and a lot of other industries for that matter) consider standard practice: treating stakeholders as intelligent participants rather than passive recipients of carefully curated but often flimsy words.

Explain

How big ideas are translated into words that resonate, build identity and set the context for a smart conversation.

How Jonathan Anderson rewrote the definition of luxury for the current climate

Sure, you’ve read plenty about it by now and – while not particularly jaw-dropping – the new Dior collection really is that good. For those of us who have loved a sartorial button up with jeans and a blazer, it could be argued this is important vindication. Chris Black and SKMG share this in common.

But beyond dressing A$AP Rocky exceptionally (even by his standards), Anderson’s approach represents a fundamental departure from traditional luxury communication, and the result highlights what has been broken in the way most luxury houses have explained themselves of late.

To understand the full picture we need to go back to Loewe. The way JW operated his first major luxury house versus most is telling. Traditional luxury communication emphasises lineage: “We've been making beautiful objects for X decades, therefore you should desire them”. Anderson inverted this logic: “Here's how we make beautiful objects, here's why these techniques matter, here's how you can appreciate craftsmanship.”

When Anderson took over Loewe in 2013, it was a relatively forgotten Spanish leather goods and fashion house that most people couldn’t distinguish from dozens of other heritage brands trading on vague notions of European craftsmanship. Today, Loewe represents craft and quality first, not Spanish leather goods heritage or founding family mythology. The result? Loewe's annual revenue rose from approximately €230 million in 2014 to between €1.5 and €2 billion in 2024. But more importantly, research shows how Anderson significantly shifted consumer perception.

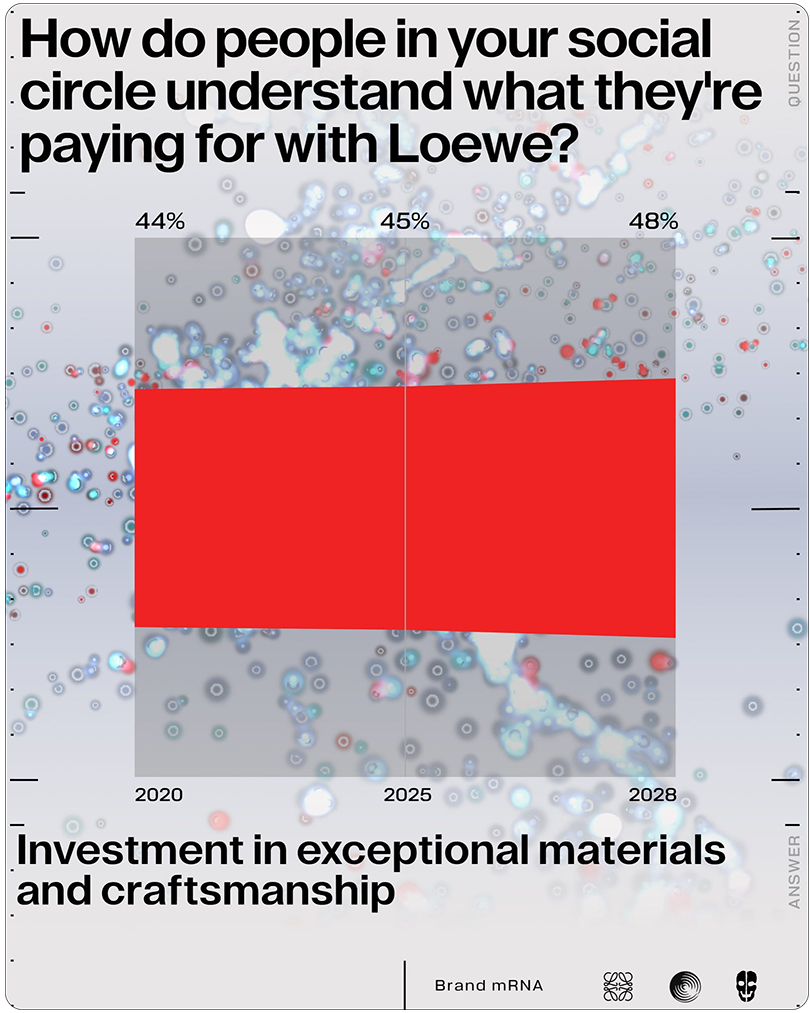

According to Dot Dot Dot’s Brand mRNA survey on the 175-year-old Loewe brand, when asked what people believe they’re paying for when buying Loewe, 45% said “investment in exceptional materials and craftsmanship” – a figure that has climbed consistently over five years. Only 38% said “connection to heritage and historical significance”.

The data demolishes the luxury industry’s core assumption that heritage storytelling drives buying decisions. These days, people respond to explained value rather than assumed mystique. They want to understand how something is made, why it costs what it costs, and what makes it different – not which aristocrat carried the original version in 1846.

Anderson was forensically focused on craft explanation. Product launches explained construction techniques in detail. The Puzzle bag required over 500 individual steps to assemble and Anderson made sure customers understood the complexity. Social feeds documented behind-the-scenes manufacturing processes. Fashion shows became immersive environments where audiences could witness artisan collaboration in real-time.

Ana Andjelic’s research on fandom provides the theoretical framework for understanding why Anderson’s approach works where traditional luxury fails. As she says: “Modern brand power is in adopting fan behaviours and in treating its audience as fans.” Her analysis of Japanese denim culture reveals how passionate communities can transform entire industries through interpretive engagement with brands.

Anderson understands this instinctively. Rather than treating customers as passive recipients of luxury products, he cultivates fans who become active participants in brand culture. In Dr Marcus Collins terms, he has made purchasing a piece of clothing a symbol that you belong to a tribe with a shared appreciation for craft innovation and creative process.

Subverting expectations of how a luxury brand explains heritage is all well and good when it’s reinventing a largely forgotten house where financial performance – let alone growth – is a bonus. But Dior is a very different beast. What does JW do when given the reins of a major string in LVMH’s bow, one where financial performance is non-negotiable?

He reads the room.

Industry observers expressed relief that Anderson’s Dior delivered pieces that felt genuinely wearable across customer segments, but the real achievement was how he made formal luxury feel accessible without dilution. In an economy where expenditure on avant garde luxury fashion is reduced, JW offers high-quality pieces with real wearability – real craft value – this time with tiny details to signal authenticity.

Reinventing the lipstick effect but keeping the brand on the rails of its roots, he offered more affordable slip-on sneakers dotted with shamrocks, or iconic ties that allow the fashion kids to buy in and signal the collection is cool to those with more disposable income prepared to drop higher $$$ on green half-zips, sweaters and jeans bearing the same tiny embroidered details. Each piece invited participation rather than demanding reverence.

Sure, there’s a valid suggestion that the styling will only serve to boost sales of similar items at Ralph Lauren, Auralee, Buck Mason or J. Crew, but the subtle cues that have begun spinning a new design language for JW’s Dior will definitely attract people who want the real deal.

Anderson’s approach shows exactly how contemporary relevance requires different communication skills than traditional luxury marketing: instead of creating mystique through withholding information, successful brands build authority by sharing knowledge.

The framework operates on four principles that pretty much any luxury brand can implement:

Product launches < brand education

Help audiences understand manufacturing complexity, material sourcing decisions and artisan collaboration processes rather than assuming they should trust “brand expertise” without explanation.

Heritage < process

Focus storytelling on how things are made rather than how long brands have been around. People want to justify purchases rationally as well as emotionally, requiring brands to explain why techniques matter and how customers can appreciate craftsmanship. Check out this LinkedIn post from Andrew a few months back where he spoke about Hermés doing a similar thing.

Hierarchy < community

Create relationships that feel collaborative rather than condescending. Feature diverse voices to demonstrate that luxury consumption represents cultural participation rather than status acquisition.

Accessibility ≠ dilution

Make luxury feel attainable without compromising quality standards. Maintain premium positioning while creating entry points for different customer segments, ensuring that lower-priced items reflect the same craft standards as premium offerings. See the next section for more on how this is being reinvented through experience.

An important note: the lipstick effect is dead

Since we’re on the lipstick effect, Beth Bentley's analysis of the "lipstick index" evolution is worth getting into. She explains how luxury brands – JW excluded – misunderstand contemporary consumer psychology. Leonard Lauder's famous theory held that lipstick sales spiked during economic uncertainty because consumers sought affordable indulgences when larger purchases felt impossible. But during the pandemic, lipstick sales fell 15% in 2020, breaking the correlation entirely. As Bentley explains, people haven’t stopped buying little indulgences, they are just spreading their bets across £8 oat matcha lattes, £15 gummies, Amazon Prime impulse buys, and TikTok Shop flash sales. The psychology remains identical – claiming moments of self-agency during anxious times – but the objects have completely diversified.

This shift from the singular “lipstick index” to what Bentley calls the “Argggh! Index” reflects a fragmented market where small luxuries prosper because we’re feeling perpetually stressed rather than during specific crisis moments. For luxury brands, this means accessible entry points like Anderson’s €250 ties serve the same psychological function as Lauder’s lipsticks, providing cultural currency and emotional relief without requiring major financial commitment.

That’s going to be important to remember when we hit Amplify by the way.

Amplify

A conversation means someone has to listen and respond. Cleverly amplifying the message to the right audience, at the right time, is the final piece of the puzzle.

Luxury pop-ups are booming, baby.

Why? Controlled access to experiences creates more desirability than restricted access to products. This is the modern evolution of the traditional theory behind more affordable cosmetics lines from luxury houses.

The key difference is the understanding that experiences afford conversations, across TikTok, across discord, Instagram, print magazines and – woe betide – between actual people. An exclusive experience is a hell of a thing to share online, and by proxy, a powerful tool for a brand to get a message out through participation.

Pop-up success depends on balancing accessibility with selectivity. Brands must create entry points for different audience segments while maintaining premium positioning. The most effective activations operate like cultural institutions rather than retail spaces, offering education, artistry and community engagement alongside purchase opportunities.

When pop-ups collaborate with regional artists, source materials from local suppliers or integrate community organisations, they generate organic cultural integration rather than imposed brand presence.

The Louis Vuitton x Murakami activation in Singapore’s heritage district earlier this year demonstrated this approach. By putting the experience within UNESCO-recognised cultural context and making it the only Southeast Asian location, the brand created geographic significance that enhanced rather than diluted luxury positioning.

Then there’s Burberry’s very recent takeover of Somerset’s iconic estate, The Newt, which doubled down on the brand’s affinity with the countryside and “the essence of a great British summer”. This kind of activation works because it is rooted in place. It’s partnering with a historically significant site (think heritage gardens, farm-to-table dining and total rural luxury) something that allows the brand to fuse its identity with a lived, local culture. This kind of cultural immersion invites guests to become, effectively, storytellers that generate amplification through their presence alone.

Local partnerships also provide amplification through community networks that brands cannot access independently. Regional influencers, cultural institutions, and media outlets become invested stakeholders rather than paid promotional channels, generating authentic coverage that extends reach organically.

Zooming out: the new luxury is service-first

Before we round out the issue, it’s worth exploring the fact that things aren’t limited to fashion: luxury’s centre of gravity is shifting across the board. Increasingly, luxury is about what your lifestyle unlocks. It’s being redefined by how well a brand anticipates your needs before you articulate them. Nowhere is this shift clearer than in the rise of branded residences sector (polar opposite of the above discussion on the affordability scale but equally as important), where buyers are investing in access as much as they are granite splashbacks or nameplate doorbells. Luxury has shifted from being a thing you own to a feeling you receive. Checkout this Aston Martin residence in Minami-Aoyama. It’s the first branded residency to hit Tokyo, and if an increased demand for exclusively crafted luxury you can live in is indeed on the horizon, it’s our bet you’re about to hear a lot more of these dominating Asia-Pacific.

Picks & Recs

Our esoteric celebrity-style favourites

Basquiat inspired JW Anderson to revive the single-collar-tie-tuck, here’s who we’re turning to for niche tips.

Andrew

The G Dragon headscarf:

Sam

Cameron Diaz hair:

Neil

Wannabe celebrity (and talented videographer) Bill Mansfield and the ugliest shirt ever, a constant reminder of what to avoid. Note the wallpaper in the photo on the right: