Kendrick and Drake: in reflection

Has there ever been as clear a loser as Drake?

Kendrick’s playing the Superbowl and Drake gets, well, this New Yorker article opening with a less-than-subtle question:

Has there ever been as clear a loser as Drake?

At the time of the roaring ‘20s greatest episode of rap fisticuffs (calling it early) opinions were split, but several months after the Drake v Kendrick beef, the victor is pretty clear. Just check the charts.

No, we’re not going to rehash a play-by-play of the title fight. But it is interesting to look at where Drake went wrong and what businesses might be able to learn from an apparently unrelatable mega star. Specifically, how he fell out of conversation with his audience.

1.Act

It’s not a smart conversation if there’s nothing to talk about.

Start with the right strategy and execution to prove you can walk the talk.

When is enough enough?

A passage from the afore-mentioned New Yorker article reads:

In the past, stars searching for a narrative reset likely would’ve looked to a national magazine profile, a “Saturday Night Live” hosting spot, or a Netflix documentary. But, in 2024, Drake has landed on the modern solution of flooding the Internet with content. Last month, he released a documentary-cum-data dump, 100 Gigs for Your Headtop, a low-tech Web site with a list of alphabetized folders featuring new music, unused promotional material, and nearly eighteen hours of behind-the-scenes footage dating back to 2010. (Recently, he uploaded more content to the site, much of it from recording sessions for the 2013 album “Nothing Was the Same.”)

Although the clips are bunched into loosely organized groups, there’s no shape or structure to them, no clear way to discern what matters and what doesn’t. In the first dump, we see Drake as an attentive father, walking with his toddler across an empty stage; we also see him as a caring friend, dapping up his bros and saying he loves them. Other clips depict him as an obsessive artist, poring over every detail, incapable of leaving the studio, and as a benevolent and jovial kingpin with a private plane and a distressing number of tracksuits, a hookah always smoldering. When women appear, they’re strippers counting money in the club or dancers doing choreography to Drake songs. In the subsequent dump, which features content from a few years prior, we see a charming, idealistic version of Drake, a wide-eyed kid desperate to actualize his greatness.

Is it wise to give your fans everything? Radical transparency is in. Gen Z will choose an authentic, lo-fi chat to camera 10 times over anything curated, or more polished. Check out any megastar sub-25 and their feeds will be a haphazard series of photo-dumps that span screenshots, selfies, lo-fi memes and God knows what. It’s laconic, nonchalant and riddled with layered references.

It’s a stark contrast to the days of colour-curating an Instagram feed with heavily edited, professionally taken one-shots.

The article – correctly – name-checks T-Swift and Post Malone as great examples of artists who have demonstrated this maximalist strategy in releasing music, with multiple vinyl editions or albums that exceed 30 tracks (followed by surprise albums).

Part of the reason this stuff is in vogue is something we chatted about in our Heartbreak High issue. Subcultures, particularly those online, are fostered and grown through discourse, analysis and repurposing of content. In the case of Heartbreak, by leaning into the Australianisms, the show sparked curiosity among foreign audiences. Viewers went the extra mile to get to the bottom of all the Easter Eggs and the result was a deluge of user-generated content around the show’s language.

Remember this: If you give your audience more content that encourages them to discover something new and compelling, they will do the work. Especially if it gives them some inside knowledge or lingo they can reproduce as proof of their cultural subscription.

Back to the point: Drake didn’t do that.

The article continues:

This suggestive, fragmented presentation of self is what 100 Gigs captures: Drake positioning himself as genial and gracious, boisterous and beloved, so in on the joke he’s exempt from ever being the butt of it.

And yet what the dump does not communicate is the fabric of Drake’s inner life. In a collection of tour footage from the first dump, we see him lead prayer circles before taking the stage: “I’m gonna go out there and do exactly what you put me on this earth to do,” he tells God, as hired hands huddle around him. “Just take a seat and watch.” The rare dives into Drake’s psyche arrive during informal interviews with close collaborators like Noah (40) Shebib. He mentions his friend’s “psychotic” ambition, his maturation as an artist, and his pivot to more “aggressive” music, but he resists dissecting Drake further, even when gently prodded.

Rather than giving an authentic glimpse into anything compelling outside of the stratospherically unrelatable chest beating in Drake’s most recent music that smacks of unprocessed insecurity (more on that later), he’s just given audiences more of what they already know. Like. Just so much more. It’s careful curation enmasse trying to be authentic. It’s not walking the talk, it’s acting in a script he’s written and passing it off as reality TV… so actually, it’s just reality TV.

Like everything else in this game, do it if it creates value, not to cover your ass.

For people to want to immerse themselves in a world, you need to give them threads to pull on, and lines to read between, and allow them to engage in their own cultural production (see how the K-pop fandoms do it).

But giving them a ceaseless barrage of self-centred sermons, around the clock, Big Brother-esque, live-stream diary-style update of your every thought, as our boy Drake is so fond of doing? It doesn’t really invite anyone to dig deeper and deeper, or create an edit to share with the fanclub. You’re neutering the chance of audience curiosity. Worse, you’re giving them ample chance to grow bored of you.

2.Explain

The way those big ideas are distilled into words that resonate, build brand identity and nail the message.

There was a time when Drake stood out in the world of hip-hop not just for his hit-making prowess, but for his vulnerability. He was the rapper who dared to be transparent about his insecurities, heartbreaks and awkward emotional moments. He was almost too in touch with his sensitive side.

Just look at his early lyrics (we’ve outlined some below, don’t fret). They were cringingly self-reflective, capturing the attention of listeners who found his honesty refreshing. It was this willingness to bare his soul — whether confessing his loneliness or admitting his flaws — that made him feel relatable.

Dare we say it, Drake’s sentimentality made him the “everyman’s rapper”. with a rise to fame not dissimilar to Donald Glover – a self-aware sitcom kid turned musical superstar – being someone grappling with their fame while staying grounded. Disclaimer: there isn’t a single person at SKMG who doesn’t agree Donald Glover is an arbiter of excellent taste and aspirational creative output. It hurts us to mention him in the same sentence as Drake as much as it hurts you to read it, but the point stands.

But somewhere along the way, something shifted. Badly. Drake’s lyrics are now largely flexes about his wealth, his luxury cars, and his women. His persona has morphed into that of an untouchable superstar who seems more concerned with showing off his riches than connecting with his audience. In fact, many of his more recent lyrics — about gambling, cosmetic surgery and substance abuse — have alienated the very fans who once saw themselves in his songs. Instead of the humble guy struggling with fame, we now have a man whose insecurities seem to fuel a hollow display of excess. It’s pity the reader in sheep’s clothing; you’re supposed to envy him, but the more effort he puts into stunting, the less likeable he becomes. It’s a narrative that feels more like a cautionary tale of ego than an evolution in artistry.

Harping back to 2009 where, in his song Fear, he writes, “I pop bottles ’cause I bottle my emotions”, a line that reflects a man aware of his flaws, even as he struggles with them. Now contrast that with 2018's “I want Saudi money, I want art money / I want women to cry and pour out they heart for me / And tell me how much they hate it when they apart from me” from Dreams Money Can Buy and the shift is stark but not in a good way. The emotional transparency is gone, replaced by the kind of shallow self-importance that does little more than remind us that Drake is rich, and we are not. Where he once played the everyman navigating his own neuroses, he's now playing a caricature of the celebrity rap star, alienating a large part of his fan base.

But there’s more: In Marvin’s Room (2011), Drake confesses, “I’ve had sex four times this week, I’ll explain / Having a hard time adjusting to fame” which, sure is still a bit much, but he’s self-aware. It exposes a man struggling with the weight of his newfound success. Compare that to Rich Flex (2022), where he boasts “Can you hit a lil’ rich flex for me?” The new Drake isn’t just rich; he’s desperate for you to know it. The vulnerability has disappeared, replaced by an inflated ego that offers little to the audience but a hollow display of affluence.

It’s the classic case of a brand or persona evolving from quirky and relatable to an inaccessible megazord of self-importance — no longer someone you want to have a beer with, but someone whose existence seems predicated on flaunting what you don’t have.

And the tragedy? We liked him better when he was openly crying into his wine.

Having said that

This is not the first instance of celebs explaining their affairs in unrelatable ways, and it certainly won’t be the last, just look at these apologies.

3.Amplify

It’s not a conversation if no one’s listening. Cleverly amplifying the message to the right audience, at the right time, is the final piece of the puzzle.

When you’re trading punches, it’s not always about how hard you can hit, but how loud.

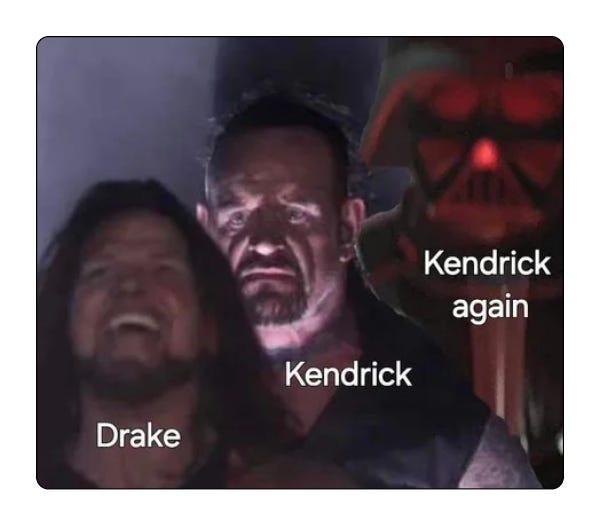

A huge part of Kendrick’s success in this whole fandangle comes down to the objective scoreboard: Kendrick’s streaming numbers during his feud with Drake were significantly larger across platforms. Not Like Us garnered over 70 million streams on Spotify in just a couple of weeks, while Drake’s Push Ups only reached around 40 million in the same time frame. Even tracks like Kendrick’s Euphoria pulled in 60 million Spotify streams compared to Drake’s more sluggish performances like Family Matters, which managed around 20 million streams in its first week.

How did Kendrick win the battle? Timing, strategy, and knowing when to hit hard and when to hold back are essential to staying ahead. Kendrick knew his audience and how to leverage every platform to create a narrative that would stick. In contrast, Drake’s approach was sluggish and lacked precision, letting Kendrick seize control of the conversation.

It’s not enough to release good content. You need to drop it in the right places, at the right time, and with a clear sense of who’s going to consume and share it. Kendrick leveraged platforms like TikTok, Instagram and Spotify, knowing these were spaces where his core audience already lived.

Not Like Us became a viral sensation because it didn’t just live on the charts — it thrived in memes, sound bites, and TikTok challenges. Kendrick knew how to make his content irresistible, turning fans into marketers. It wasn’t just the song that was shareable; it was the art, the message, and the controversies. He made it easy for his audience to become the amplification engine. In short: the tracks hit louder because Kendrick remembered the point of actually releasing music. He did it for the fans.

On the other hand, Drake’s response was late and scattershot. Once again, the 6 God jumped in to prove his own delusions of grandeur rather than put out something the fans wanted. Push Ups and Family Matters failed to hit as hard because they felt like afterthoughts — neither were positioned for virality. They weren’t easy to share, didn’t resonate visually, and weren’t positioned for TikTok or meme culture, which is ironic given Drake’s former prowess on the platforms.

Drake missed the social amplification that Kendrick nailed. A good publicist or brand strategist would tell you that the story isn’t just in the content; it’s in the delivery. Drake played catch-up, while Kendrick controlled the narrative by saturating the right channels at the right time, with content that was built to travel.

Speed, timing and channel selection are critical. Drop your message when it will have the most impact, like Kendrick did, and stack your releases to keep the momentum going. Whether it’s a marketing campaign or a PR response, keeping your message alive in the minds of your audience — before the competition has time to react — is essential.

Back in the Cola Wars it was the same deal. Pepsi mastered timing and youth-orientated messaging to dominate Coke in the ’80s with The Pepsi Generation in 1984, becoming a cultural force and positioning itself as the brand for young, energetic consumers. The results? By the end of the decade, Pepsi in the US had gained a market share increase of nearly 10%, capturing up to 20% of the total soft drink market there during some quarters. This youthful image catapulted Pepsi past Coke in consumer perception among young drinkers, even if Coke still maintained the overall sales lead in many regions.

Pepsi didn’t just release a campaign: it created a movement. It hit Coke hard by capitalising on where its target audience was consuming media, including music videos, concerts, and television, amplifying their message across youth-centered platforms. Coke’s traditional response wasn’t enough to regain the cool factor Pepsi had claimed.

Don’t just wait for the fight to come to you. Time your punches, use the right platforms and make sure your message is impossible to ignore. If you do, the competition won’t even know what hit them.

Picks & Recs

OUR FAVOURITE DISSES,

ACROSS HISTORY

It might be the romanticism of the letter medium, but there’s something so scathing about a typed out formal piece that punches that much harder. And it’s from Angus & goddamn Robertson.

A chronically-online Matty Healy inserting himself into a 20-year standing beef between the Gallagher brothers (only weeks before the final bell rang mind you) was truly a gift made in Mancunian heaven.

Truman Capote when a drunk at a bar asked his to autograph his penis: “I don’t know if I can autograph it. But perhaps I can initial it.”

Dorothy Parker was on her honeymoon when Harold Ross, an editor for New Yorker, asked why she was late with a book review: “I'm too fucking busy, and vice versa.”

Dorothy Parker when a drunk man said to her that he couldn’t bear fools: “Apparently, your mother could.”

Dorothy Parker who also took a shot at former president Calvin Coolidge. When told Coolidge had died, Parker asked “How can they tell?”

Dorothy Parker who was also known to remark, “All men are the same age.”

Just anything Dorothy Parker has said, really.

Ed Koch when a reporter asked him to explain a statement he had issued: “I can explain this to you; I can't comprehend it for you.”

Elizabeth Taylor when asked about her male co-stars: “I reckon some of my best leading men have been dogs and horses.”